A Refutation of David Marshall's Book Rebuttal of My OTF, Part 1

I've decided to write more than just one post about Dr. David Marshall's “rebuttal” to my book The Outsider Test for Faith (OTF). I will attempt to show why Marshall's book, How Jesus Passes the Outsider Test: The Inside Story, is really bad. In fact, it's so bad I'm using the word "refutation" for what I'm about to do to it. I hardly ever use that word because refutations are usually unachievable in these kinds of debates. If I'm largely successful then it also says something about Dr. Randal Rauser, that he will say and endorse anything in order to defend his Christian faith. No educated intellectual worthy the name would have written Marshall's book. No educated intellectual should think it's worthy of any kind of a blurb either. Rauser blurbed it saying, “Delightful riposte . . . rhetorical wit and the cosmopolitan vision of a true world citizen!” On his blog Rauser additionally recommended it saying, "While I don’t think much of Loftus’s faltering attempt to make an enduring contribution to serious academic discourse, I do think highly of Marshall’s eloquent rebuttal of it." Drs. Miriam Adeney and Ivan Satyavrata also recommend Marshall's book.

is really bad. In fact, it's so bad I'm using the word "refutation" for what I'm about to do to it. I hardly ever use that word because refutations are usually unachievable in these kinds of debates. If I'm largely successful then it also says something about Dr. Randal Rauser, that he will say and endorse anything in order to defend his Christian faith. No educated intellectual worthy the name would have written Marshall's book. No educated intellectual should think it's worthy of any kind of a blurb either. Rauser blurbed it saying, “Delightful riposte . . . rhetorical wit and the cosmopolitan vision of a true world citizen!” On his blog Rauser additionally recommended it saying, "While I don’t think much of Loftus’s faltering attempt to make an enduring contribution to serious academic discourse, I do think highly of Marshall’s eloquent rebuttal of it." Drs. Miriam Adeney and Ivan Satyavrata also recommend Marshall's book.

Here we go then, little ole me against four, count 'em, four Ph.D.'s. What chance might I have? How dare I even try?

Previously I had written something briefly in response to Marshall's chapter on the OTF in the book True Reason: Confronting the Irrationality of the New Atheism. I was thankful that at a minimum he embraces it (with caveats) against Victor Reppert, Randal Rauser, Matthew Flannagan, Norman Geisler, Mark Hanna, Thomas Talbot and some others. LINK I was planning on writing a longer response but didn't get around to it. Now I don't need to, for the Arizona Atheist (AA) has done so. He said:

For anyone interested I have previously had extended discussions/debates with several Christian scholars who refuse to see the simplicity and importance of the OTF. Here are three of them:

--David Marshall on the OTF.

--Randal Rauser on the OTF.

--Matthew Flannagan on the OTF. [I had recently said on Justin Brierley's "Unbelievable?" program that Flannagan's review of the OTF was the most ignorant and dishonest of them all. The linked posts show you why I think that. I show this in my book too.]

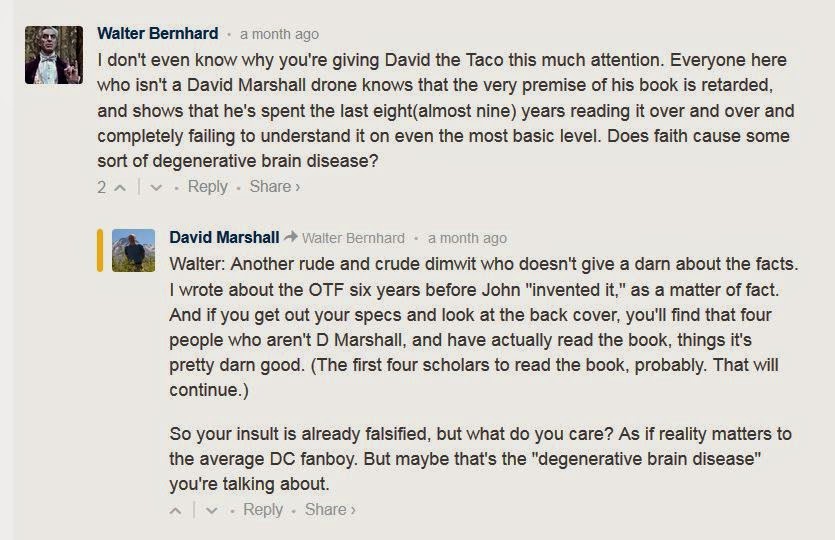

I want to start out by correcting some egregious errors of Marshall. You should know first that he erroneously claimed to have written about the OTF six years before I did right here. Below are the screen shots:

I don’t claim to have invented this test, since it has been bandied about for millennia wherever there were skeptics. I do claim to have defended it better than anyone else, as far as I can tell. I read what Marshall said in his 2000 book. He repeated it on pages 182-83 of this new book I’m refuting. There is nothing he said that had not been said before him by G.K. Chesterton, using different words. It is merely a repackaged Chesterton, which Marshall did not acknowledge as coming from him. I argued on pages 26-27 in my book that what Chesterton said does not resemble the OTF at all though. At the same time what Chesterton said is still worthwhile, a good statement for believers to take seriously. Josh McDowell takes it one step further. He travels around the country challenging Christians to refute their own faith. His former protégé, Dustin Lawson, did just that and as a result he no longer believes.

Another of the many errors of Marshall’s is that he says I present the OTF “as an argument against Christianity.” (p. 7.) Now I do think the OTF is a good argument against faith, but in my book I go overboard to say it's merely a test for faith. I demand Marshall to show us book chapter and verse where I say anything different. He cannot do that. There are three stages in OTF argumentation: 1) First we must acknowledge the problem of religious diversity and dependency, 2) Next we should accept the test as the best and only alternative to know which religion is true, if there is one; then and only then 3) we can debate faith based on the test. In the second stage I argue the test is neither unfair nor faulty. It allows for a faith to pass the test, as well as for all faiths to fail the test. In the third stage I argue the test shows Christianity fails the test, but that’s not actually part of accepting the test itself.

I find that people who disagree with a reasonable non-double standard test for religious faith cannot be reasoned with, for obvious reasons. How we test a truth claim has a great deal to do with the kind claim we're testing. Sometimes a poll can settle one type of claim. Other times we can settle a different claim by traveling somewhere. Counting spoons can test a certain type of claim, while sitting on a fluffy pillow can test a different one. Logic and/or math can test other types of truth claims. In testing some types of claims we rely heavily on one discipline of learning, while testing other claims we rely heavily on other disciplines of learning. Some claims demand testing from several different academic disciplines. It depends on the type of claim we're testing that determines how we test it.

I spoke to a group of students (including two ministers) at Wabash College in Crawfordsville, Indiana. I started by asking them this question: "How many of you know which religion is true?" A few hands were raised. I continued, "How sure are you that your religion is true?" The overwhelming response was "100%". It's the typical response when it comes to religious faith because faith is basically immune from testing. It has no method for determining truth. With faith anything can be believed or denied without any evidence at all. No wonder there are so many mutually exclusive religions in the world. Testing one's religious faith is anathema to the minds of overwhelming numbers of believers since faith pleases their imagined gods. Of course it does! Faith pleases the gods because the gods cannot allow testing. They cannot allow testing because the gods are all made up by kings, priests, prophets, philosophers, guru's, shamans, witchdoctors and so forth, who only want blindly obedient followers. In some cases the gods ask believers to test them (see Malachi 3:10), but those tests are not real ones given the plethora of cognitive biases human beings have to count the hits, and to discount the misses.

So how can believers test their faith should they really want to know if their religious faith is true, given the nature of religious faith? With the The Outsider Test for Faith. There is no better alternative. If you think there is one then what is it? It's the type of test geared to test religious faith just as geologists test the age of the earth with rock samples, just as neurologists test brain states with CAT scans, just as economists test economical theories with the results of economical policies. You cannot test the age of the earth with a CAT scan, nor can you test economical theories with rock samples. We develop appropriate tests for each different truth claim being tested. It's that simple.

There is no better alternative. If you think there is one then what is it? It's the type of test geared to test religious faith just as geologists test the age of the earth with rock samples, just as neurologists test brain states with CAT scans, just as economists test economical theories with the results of economical policies. You cannot test the age of the earth with a CAT scan, nor can you test economical theories with rock samples. We develop appropriate tests for each different truth claim being tested. It's that simple.

A third error of Marshall’s is that he dismisses my understanding of religious diversity as “superficial.” He opines that this is the “most essential problem with Loftus’ version of the OTF.” (p. 10). He tries to inform the uninformed that the diversity of faiths “is genuine, but in some ways superficial. As Chesterton noted, religions around the world commonly included four beliefs: in God, the gods, philosophy, and demons.” Agreeing, Marshall says, “Peel away labels, and many beliefs seem to be universal or at least widespread.” Then he concludes, “If widespread disagreement renders a religious tenet less credible, then agreement must render it more credible. One cannot make the argument, without implicitly admitting the other as well.” (p. 18-19)

Now in what follows I aim to hold him to that. Either "widespread disagreement renders a religious tenet less credible" or not. I'll deal with his claim that agreement must render something more credible later, and dispute it depending on the issue to be solved.

Marshall should know there are major disagreements even about these four minimal beliefs. Religionists accept the existence of one Supernatural Being (i.e., one God), or they accept many Supernatural Beings (gods, goddesses, angels, spirits, ghosts, demons) or they accept one Supernatural Force (Process theology, Deism) or many Supernatural Forces (i.e., karma, fate, reincarnation, prayers, incantations, spells, omens, Voodoo Dolls), or some sort of combination of them. Religionists also disagree with each other over who these Beings and/or Forces are, how they operate, and for whom they operate. Everything else is up for grabs. When it comes to the Devil, for instance, only some versions of Christianity accept his existence. And philosophy? Define it and we all do it, all of us. So there is nothing significant in recognizing we should all love wisdom. What we should look for is whether or not we agree when we think about the nature of nature. And it’s clear we don’t.

I’m really at a loss to respond to what Marshall said about me, given what the reader will find quoted on pages 34-36 of my book. I'm tempted to ask if he can even read. Take a look:

Professor of anthropology David Eller tells us, as I quoted in my book, that

The problem of religious diversity is so bad that Robert McKim tells us,

And Marshall, either "widespread disagreement renders a religious tenet less credible" or not. Does it?

This is getting too long. Done for now. The best is yet to come.

Here we go then, little ole me against four, count 'em, four Ph.D.'s. What chance might I have? How dare I even try?

Previously I had written something briefly in response to Marshall's chapter on the OTF in the book True Reason: Confronting the Irrationality of the New Atheism. I was thankful that at a minimum he embraces it (with caveats) against Victor Reppert, Randal Rauser, Matthew Flannagan, Norman Geisler, Mark Hanna, Thomas Talbot and some others. LINK I was planning on writing a longer response but didn't get around to it. Now I don't need to, for the Arizona Atheist (AA) has done so. He said:

Each of David Marshall’s arguments against the OTF fail. His next tactic, regardless of how illogical it may be, is to argue that Christianity has passed the OTF “billions of times.” (59) If an argument is by its nature “flawed,” as Marshall contends, how then, can he possibly believe arguing that “billions” allegedly passing this flawed test is proof that Christians have come to their faith in a rational manner? See more here.There is a lot in Marshall’s book length treatment of the OTF that was in that chapter. So much the better for what AA said.

For anyone interested I have previously had extended discussions/debates with several Christian scholars who refuse to see the simplicity and importance of the OTF. Here are three of them:

--David Marshall on the OTF.

--Randal Rauser on the OTF.

--Matthew Flannagan on the OTF. [I had recently said on Justin Brierley's "Unbelievable?" program that Flannagan's review of the OTF was the most ignorant and dishonest of them all. The linked posts show you why I think that. I show this in my book too.]

I want to start out by correcting some egregious errors of Marshall. You should know first that he erroneously claimed to have written about the OTF six years before I did right here. Below are the screen shots:

I don’t claim to have invented this test, since it has been bandied about for millennia wherever there were skeptics. I do claim to have defended it better than anyone else, as far as I can tell. I read what Marshall said in his 2000 book. He repeated it on pages 182-83 of this new book I’m refuting. There is nothing he said that had not been said before him by G.K. Chesterton, using different words. It is merely a repackaged Chesterton, which Marshall did not acknowledge as coming from him. I argued on pages 26-27 in my book that what Chesterton said does not resemble the OTF at all though. At the same time what Chesterton said is still worthwhile, a good statement for believers to take seriously. Josh McDowell takes it one step further. He travels around the country challenging Christians to refute their own faith. His former protégé, Dustin Lawson, did just that and as a result he no longer believes.

Another of the many errors of Marshall’s is that he says I present the OTF “as an argument against Christianity.” (p. 7.) Now I do think the OTF is a good argument against faith, but in my book I go overboard to say it's merely a test for faith. I demand Marshall to show us book chapter and verse where I say anything different. He cannot do that. There are three stages in OTF argumentation: 1) First we must acknowledge the problem of religious diversity and dependency, 2) Next we should accept the test as the best and only alternative to know which religion is true, if there is one; then and only then 3) we can debate faith based on the test. In the second stage I argue the test is neither unfair nor faulty. It allows for a faith to pass the test, as well as for all faiths to fail the test. In the third stage I argue the test shows Christianity fails the test, but that’s not actually part of accepting the test itself.

I find that people who disagree with a reasonable non-double standard test for religious faith cannot be reasoned with, for obvious reasons. How we test a truth claim has a great deal to do with the kind claim we're testing. Sometimes a poll can settle one type of claim. Other times we can settle a different claim by traveling somewhere. Counting spoons can test a certain type of claim, while sitting on a fluffy pillow can test a different one. Logic and/or math can test other types of truth claims. In testing some types of claims we rely heavily on one discipline of learning, while testing other claims we rely heavily on other disciplines of learning. Some claims demand testing from several different academic disciplines. It depends on the type of claim we're testing that determines how we test it.

I spoke to a group of students (including two ministers) at Wabash College in Crawfordsville, Indiana. I started by asking them this question: "How many of you know which religion is true?" A few hands were raised. I continued, "How sure are you that your religion is true?" The overwhelming response was "100%". It's the typical response when it comes to religious faith because faith is basically immune from testing. It has no method for determining truth. With faith anything can be believed or denied without any evidence at all. No wonder there are so many mutually exclusive religions in the world. Testing one's religious faith is anathema to the minds of overwhelming numbers of believers since faith pleases their imagined gods. Of course it does! Faith pleases the gods because the gods cannot allow testing. They cannot allow testing because the gods are all made up by kings, priests, prophets, philosophers, guru's, shamans, witchdoctors and so forth, who only want blindly obedient followers. In some cases the gods ask believers to test them (see Malachi 3:10), but those tests are not real ones given the plethora of cognitive biases human beings have to count the hits, and to discount the misses.

So how can believers test their faith should they really want to know if their religious faith is true, given the nature of religious faith? With the The Outsider Test for Faith.

A third error of Marshall’s is that he dismisses my understanding of religious diversity as “superficial.” He opines that this is the “most essential problem with Loftus’ version of the OTF.” (p. 10). He tries to inform the uninformed that the diversity of faiths “is genuine, but in some ways superficial. As Chesterton noted, religions around the world commonly included four beliefs: in God, the gods, philosophy, and demons.” Agreeing, Marshall says, “Peel away labels, and many beliefs seem to be universal or at least widespread.” Then he concludes, “If widespread disagreement renders a religious tenet less credible, then agreement must render it more credible. One cannot make the argument, without implicitly admitting the other as well.” (p. 18-19)

Now in what follows I aim to hold him to that. Either "widespread disagreement renders a religious tenet less credible" or not. I'll deal with his claim that agreement must render something more credible later, and dispute it depending on the issue to be solved.

Marshall should know there are major disagreements even about these four minimal beliefs. Religionists accept the existence of one Supernatural Being (i.e., one God), or they accept many Supernatural Beings (gods, goddesses, angels, spirits, ghosts, demons) or they accept one Supernatural Force (Process theology, Deism) or many Supernatural Forces (i.e., karma, fate, reincarnation, prayers, incantations, spells, omens, Voodoo Dolls), or some sort of combination of them. Religionists also disagree with each other over who these Beings and/or Forces are, how they operate, and for whom they operate. Everything else is up for grabs. When it comes to the Devil, for instance, only some versions of Christianity accept his existence. And philosophy? Define it and we all do it, all of us. So there is nothing significant in recognizing we should all love wisdom. What we should look for is whether or not we agree when we think about the nature of nature. And it’s clear we don’t.

I’m really at a loss to respond to what Marshall said about me, given what the reader will find quoted on pages 34-36 of my book. I'm tempted to ask if he can even read. Take a look:

Professor of anthropology David Eller tells us, as I quoted in my book, that

there are many religions in the world, and they are different from each other in multiple and profound ways. Not all religions refer to gods, nor do all make morality a central issue, etc. No religion is ‘normal’ or ‘typical’ of all religions; the truth is in the diversity.When it comes to belief in god(s), Eller writes,

Many or most religions have functioned quite well without any notions of god(s) at all, and others have mixed god(s) with other beliefs such that god-beliefs are not the critical parts of the religion. . . . Some religions that refer to or focus on gods believe them to be all-powerful, but others do not. Some consider them to be moral agents, and some do not; more than a few gods are downright immoral. Some think they are remote, while others think they are close (or both simultaneously). Some believe that the gods are immortal and eternal, but others include stories of gods dying and being born . . . not all gods are creators, nor is creation a central feature or concern of all religions. . . . Finally, there is not even always a firm boundary between humans and gods; humans can become gods, and the gods may be former humans.Eller continues:

Ordinarily we think of a religion as a single homogeneous set of beliefs and practices. The reality is quite otherwise: Within any religion there is a variety of beliefs and practices—and interpretations of those beliefs and practices—distributed throughout space and time. Within the so-called world religions this variety can be extensive and contentious, one or more variations regarded as "orthodox."Eller concludes that

…religion is much more diverse than most people conceive. . . . “Religion” does not equal “theism” and certainly not “Christianity,” let alone any particular sect of Christianity. Indeed, there is no specific religion or type of religion that is really religion, the very essence or nature of religion. . . . Not only that, there is no central or essential or uniquely authentic theism but rather an array of theisms . . . . “Christianity” consists of a collection of Christianities including Catholic, Orthodox, and Protestant. And there is no central or essential Protestantism: it is a type of Christianity/monotheism/theism/religion with many branches. No one Protestant sect is more Protestant or more religious than any other. . . . In fact, there is no “real” Christianity at all, only a range of Christianities.So I do understand the nature of religious diversity. Marshall does not. For instance, there is nothing when reading Marshall's book where he shows us he understands there are various Christianities, nothing. As far as the reader is concerned he’s defending the one and only Christianity, his, without so much as telling us which one that is. If anyone has a superficial understanding of religious diversity it is Marshall. Now I know he knows different. He cannot help knowing the various denominations and spectrums of theologies among Christianities. It’s just that when it comes to calling me superficial it never occurred to him to acknowledge this fact about Christianity, something I am all too aware about. It's one of the reasons I am not a Christian, since Christians cannot agree among themselves.

The problem of religious diversity is so bad that Robert McKim tells us,

There is not a single claim that is distinctive of any religious group that is not rejected by other such groups, with the exception of vague claims to the effect that there is something important and worthwhile about religion, or to the effect that there is a religious dimension to reality and that however the sciences proceed certain matters will be beyond their scope. Obviously even claims as vague as these are rejected by nonreligious groups. (Quoted on page 40 in my book).Now someone please help me. Why am I superficial and Marshall is not?

And Marshall, either "widespread disagreement renders a religious tenet less credible" or not. Does it?

This is getting too long. Done for now. The best is yet to come.

0 comments:

Post a Comment